Sexuality

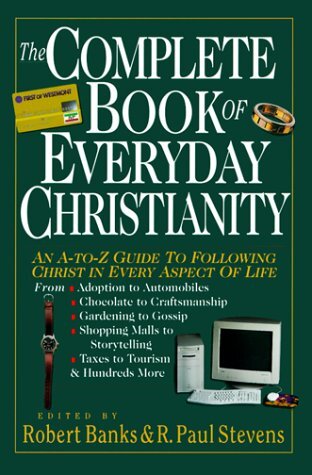

Book / Produced by partner of TOW

Contrary to the popular idea that God is in heaven shouting “Cut it out!” to any couple enjoying sexual intercourse within the covenant, God invented it, created it and blessed it saying, “It [is] very good” (Genesis 1:31). It is good biologically—reducing tensions and creating new life (see Conception). It is good socially—strengthening the capacity for love. It is good ethically—balancing fulfillment with responsibility. It is good spiritually—becoming a powerful experiential parable of Christ’s will to bless his covenant partner, the church. But crucial to the discussion of a theology and spirituality of sex is the simple observation that God says sex is good, not god! While modern people use sex, they also deify it. Their preoccupation with the genitals and the experience of sexuality betrays the fact they have made an ultimate concern out of something less than the Ultimate One. Such is the nature of idolatry. And sex makes a ready idol. In what follows, we explore what the Bible has to say about sex, its God-given purpose, how sex relates to prayer, and finally sex and singleness.

The Bible and Sex

The Bible contains references to almost every conceivable sexual experience, both healthy and sinful. Only a few references will be given here.

Divine intent. The purpose of God in creating humankind male and female is to create a community that reflects a God of love (Genesis 1:27; Ephes. 5:22, 25), to end loneliness, to communicate love within marriage (Genesis 2:18) and to continue the human race (Genesis 1:28). Married love is dignified, holy and a joy to God (Genesis 2:24; Song 1-8; Matthew 19:5-6). Single people, nevertheless, may celebrate their appetite for covenant even while not experiencing its full expression in the covenant of marriage. Many do this within a covenant community. Far from stigmatizing the single person, the New Testament offers singleness as a calling and a gift (Matthew 19:12; 1 Cor. 7:17). Sexual restraint is, however, needed whether married or single (1 Thes. 4:3-8; Hebrews 13:4) since promiscuous sex is harmful and alienates us from our Creator. Indeed sexual sins, more than most other sins, have a profound effect on our personality (1 Cor. 6:18-20) and our spirituality (Romans 1:27). A life given over to sexual pleasure is profoundly empty as people seek ever more exotic thrills to titillate their satiated desires (Jude 7-13).

The emphasis of Scripture is not only on acts but on attitudes (Matthew 5:28; 2 Peter 2:14). Sins of fantasy are as serious in God’s sight as sins in body, largely because the body is not the shell of the soul but part of the real person, as is the mind or emotions. Some references bear on the question of pornography (Phil. 4:8; 2 Tim. 2:22; 2 Peter 2:14). But in God’s sight, sexual sins are not worse or less forgivable than other sins, and there is hope of full forgiveness and substantial healing to those who have hurt themselves or others in this way (John 8:1-11; 1 John 1:9).

Covenant sex. Unquestionably sexual intercourse and its normal preparation (foreplay; Genesis 26:8) are reserved for the full covenant experience of marriage (Deut. 22:13-29). Family planning, while not named directly in Scripture, must be considered in the light of Genesis 1:28, Psalm 127:3-5 and Hebrews 13:4. The reference in Genesis 38:9 is to failing to perform a marital duty; it is not a condemnation of contraception. Premarital sex, understood biblically, is really misnamed. There is no such thing as premarital sexual intercourse. The act means marriage and is highly symbolic: the interpenetration of two lives in complete self-giving.

Sexual sin. The general word in the New Testament for unlawful and sinful sexual relationships (porneia) includes prostitution, unchastity and fornication (Galatians 5:19; 1 Thes. 4:3)—in each case the person is not treated with respect, indeed is treated rather as a sexual object. The desire is an evil desire (epithymia; Col. 3:5) or a lustful passion (pathos), connoting a preoccupation with sexual pleasure and personal gratification (1 Thes. 4:5). Several English words, including lewdness and lasciviousness, translate the word aselgeia, which means “sheer, shameless, animal lust to gratify physical desires” (Mark 7:22; 2 Peter 2:2). Obviously most of this sexual sin concerns sexual activity outside the marriage covenant, but it includes the possibility of married lust.

Prostitution treats sex as a commodity outside the covenant (Leviticus 19:29; Deut. 22:21; Proverbs 6:23-35; 1 Cor. 6:15-20), often leading to venereal disease, which is possibly mentioned in Leviticus 15:1 and Numbers 25:1-9. Extramarital sin, or adultery, while it does not reduce sexual activity to a commodity, breaks the marriage covenant and inflicts wounds on both persons (Exodus 20:14; Leviticus 20:10-14; Proverbs 5:15-23; Matthew 5:27-30), though some of these words also apply to distorted sexual expressions within marriage. While not directly dealing with sexual abuse, except in such passages as Deut. 22:22-30, the Bible provides a theological context for the profound respect of women and the relational nature of sexual acts: in Christ a woman’s body is not the exclusive possession of the husband (1 Cor. 7:3-5), and the sex act is profoundly personal (1 Cor. 6:18). Homosexual acts are an offense against the relational image of God (Genesis 1:27; Genesis 19:5; Leviticus 18:22; Romans 1:24-27)—in all these cases Scripture deals with homosexual activity rather than the tendency to homosexuality. Solo sex (see Masturbation) is not actually mentioned in Scripture, and the so-called sin of Onan (Genesis 38:9-10) is an unrelated reference. Since the Bible reveals the communal purpose of sexuality (showing love and building communion) and the danger of an unhealthy fantasy life (Matthew 5:28), solo sex must always be something less than God intended.

Sexual temptation. The Bible gives clear direction on handling sexual temptation (Genesis 39:5-10; Job 31:1; 1 Cor. 6:18; Ephes. 5:1-3) through fleeing, walking in the Spirit (Galatians 5:16) and setting our hearts on things above (Col. 3:1-14). Martin Luther once said that it is one thing to have a bird land on your head—just as sexual arousal is normal, one can hardly stop this from happening—but it is quite another thing to allow the bird to build a nest there. Becoming a Christian does not solve this problem. The power of the indwelling Christ does not anesthetize our sexual appetite. Just the reverse, new birth makes us fully alive in every conceivable way. But the cleansing love of God (2 Cor. 5:14-21) drives out unworthy thoughts and attitudes, empowers us to love (John 15:13; 1 John 4:7-21) and releases us to become truly masculine or feminine. Christians should be the sexiest people on earth precisely because their natures are being conformed to the image of God (Romans 12:1-2), because their sexual experience within marriage is physical (union), social (intimacy) and spiritual (communion), and because they are lining themselves up with God’s intended sexual design for us as human beings. Indeed there is growing empirical evidence for the fact that overall Christians are able to enjoy sex more than others and, within marriage, make better lovers!

Holy eroticism. One whole book of the Bible is devoted to the affirmation of passionate sexual love within the covenant: the Song of Songs. The Song can be considered an extended exposition of Adam’s expectant delight when he first met Eve (Genesis 2:23). Contrary to the usual interpretation that this is an allegory of Christ’s love for the church—an approach taken by Bernard of Clairvaux, who devoted his whole life as a celibate monk to expounding this allegory—this book unashamedly celebrates sexual delight. But it does not celebrate lascivious sex. An old interpretation of this book argues that there is not a single male lover (Solomon, here adding one more beautiful woman to his harem) and the Shulammite woman (noted in the New International Version by the titles Lover and Beloved), but two lovers of the same woman (Solomon and a country man to whom the woman is betrothed and for whom she longs and dreams). The woman does not want to be aroused by Solomon, as noted in the frequent refrain, “Do not arouse or awaken love until it so desires” (Song 2:7). Solomon wants to “get” love and “make” love through flattery and self-gratification. The woman, in contrast, wishes to remain faithful to her true shepherd love to whom she is betrothed (Song 6:3; Song 7:10) and for whom she searches whether in dream or reality (Song 3:1-4). Following her rebuff of the king, this true lover affirms the exclusive and holy nature of their covenant love (Song 8:6, 12). So the Song exalts faithfulness within the security of covenant; it openly encourages bodily delight where there is such reverence and loyalty; it reveals the nature of holy eroticism.

Sexual spirituality. Precisely because complementarity and cohumanity are points of our godlikeness, sexuality is also the point of our greatest vulnerability—hence the many references in Scripture to sexual sin and perversion. Ultimately the solution for sexual sin is not psychological. As Jesus noted in the case of the woman with multiple relationships, healing is found in worshiping God in Spirit (or spirit) and in truth (John 4:23-24). Tragically, the church adopted the philosophy of Neo-Platonic dualism, teaching that spirit is holy and the body is either evil or inconsequential. In contrast, Paul says the body is for the Lord and the Lord is for the body (1 Cor. 6:13), thus inviting theological reflection on our sexuality. What indeed does God have to do with genital activity, with sexual desire, with sexual differentiation as males and females, with the pleasure and playfulness of sexual activity within marriage and with the continuing sexual longings experienced by single people, whether that singleness is chosen or involuntary?

The Purpose of Sex

Answering the question “Why is there sex?” the Bible tells us six things that are enough to start a social revolution, enough to leave us ashamed that we were ever ashamed of our sexuality.

Because we crave relationship. God has designed us to move beyond ourselves. The word sex comes from the Latin secare, which literally means “something has been cut apart that longs to be reunited.” In Genesis 2:18 God says, “It is not good for the man to be alone.” Adam discovered soon enough that he needed another like himself—but different. So the male by himself cannot be fully in the image of God, nor can the female. The biblical phrase the image of God presupposes the idea of relationship. God is a Trinity, humankind a duality, of relationships. So part of our spiritual pilgrimage is to relate healthily to the opposite sex. The Roman Catholic writer Richard Rohr explains it this way:

God seemingly had to take all kinds of risks in order that we would not miss the one thing necessary: we are called and even driven out of ourselves by an almost insatiable appetite so that we could never presume that we were self-sufficient. It is so important that we know that we are incomplete, needy, and essentially social that God had to create a life-force within us that would not be silenced! (p. 30)

To consummate covenant. In the Old Testament covenants were sealed and renewed by significant rituals and signs. This signing of the covenant emphasizes that it is not an idle promise but a solemn act with serious consequences. In the New Testament the Lord’s Supper becomes the ritual of the covenant for those who belong to Jesus Christ. These rituals are like any sacraments: God communicates a spiritual grace through a material reality. Sexual intercourse is the consummation and the ritual of the marriage covenant. Just as the bread and the wine offer us spiritual nourishment, so in marriage “sexual intercourse is the primary (though certainly not the only) ritual. It is an extension and fulfillment of the partners’ ministry to each other begun during the public statement of vows” (Leckey, p. 17). Intercourse is to the covenant what the Lord’s Supper is to salvation. It expresses and renews the heart covenant. If the symbol is not backed by a full covenant, it is merely a powerless, graceless act.

To keep us distinct in unity. At the candle-lighting portion of a wedding ceremony the bride and groom, hands trembling, take the two lighted candles representing themselves and, with great solemnity, light a single central candle representing their marriage. But then they stoop down and blow out the two candles. Do they really mean to blow themselves out? Tragically, some do. One wag, hearing the familiar line “Two have become one,” asked, “Which one?” In some cases that is a rather penetrating question. Community is com-unity. The word is made up of two parts. Com means “with” or “together.” With unity, it means “unity alongside another.” It is not the oneness of a drop of water returning to the sea: sexuality is not the urge to merge. Sexuality is the urge to be part of a community of two, symbolized by the act of intercourse: one person moves in and out of another. The differences and the uniqueness of both people are celebrated at the very moment of oneness and unity. God is the ultimate mystery of covenant unity. And every family in heaven and on earth is named (or derives its origin and meaning) from the Father (Ephes. 3:14-15). Reverently we may speak of the mystery of one God in three persons; we know they are not merged. Nor do we merge in the human covenant. Partners should find, not lose, their identity.

Because male and female are complements. In a covenant marriage, each calls forth the sexuality of the other. Eve called forth the sexuality of Adam. Until she is created, the man is just “the human” (ha-adam). Only after the woman is created is he “the man” (male person, ha-ish). His special identity emerges in the context of needing a suitable helper. Adam saw Eve as one called forth. His cry “At last!” (Genesis 2:23 RSV) is an expression of relational joy. Now he has found a partner as his opposite, by his side, equal but different, his other half. C. S. Lewis compared our sexual unity to that of a violin bow and string. Both are needed, and neither can be fulfilled without the other. Speaking about the cellist Pierre Fournier, it was said that his “left hand [on the string] plays the notes and interprets the musical symbols of the score, but his right hand [on the bow] speaks, puts the emphasis, and is responsible for the interpretation” (Vancouver Symphony Orchestra). In our marriage I play the notes on the score, reading them sometimes very mechanically, while my wife, Gail, puts the emphasis, interpreting the notes. It may be different for another couple. All that matters is that bow and string together create one sound without trying to make each conform to the other.

It is important to note here that the Bible does not give us two parallel lists of qualities, one male and one female. That should be reason enough not to generalize on male and female stereotypes. The sexual act suggests that men and women are different in their sexuality. In intercourse woman receives the man, letting him come inside her. In this act she makes herself extremely vulnerable. The man, on the other hand, is directed outward. While the woman receives something, the man relieves himself of something. It means something different to the man. Perhaps it is less total for him (Thielicke, pp. 45-60). A woman needs to be psychologically prepared for this self-abandonment, not only by the public commitment of her husband to lifelong troth but also by her husband’s ongoing nurture of the love relationship. This difference in sexual identity may also be the reason behind the common male complaint that their wives do not understand their need for sexual release and expression. It is a gross but instructive overstatement to say that men must have sex to reach fullness of love while women must have love to reach fullness of sex.

To create children. Thomas Aquinas believed adultery was wrong because people having sex outside marriage do not want to conceive a child (Aquinas 11.154.11.3). Most people today do not find this a convincing argument. But face-to-face intimacy, which in intercourse only humans enjoy, is very suggestive of the nature of the relationship. Similarly, natural sex gives the procreative process its own way (which adulterers are always determined to interrupt) and is a powerful statement of why we have this appetite. Lewis Smedes says that “sex and conception are the means God normally uses to continue his family through history until the kingdom comes on earth in the form of a new society where justice dwells” (1983, p. 168). It would be wrong to say that every act of intercourse must have procreation as its end. In the Genesis narrative the man and woman were in the image of God and enjoyed profound companionship before there were children. But to cut the tie between sex and children is to reduce sexuality. A childless marriage can be a godly community on earth. But a marriage that refuses procreation for reasons of self-centeredness is something less than the God-imaging community, male and female, that was called to “be fruitful and increase in number” (Genesis 1:28). Our society treats babies as an inconvenience, an interruption to a blissful married life or a challenging career. But the Bible says that babies are an awesome wonder. Even if the birth was unexpected and unplanned for—or perhaps even, humanly speaking, unwanted—it is the work of God, a lovely mystery. Healthy sexuality makes marriage the beginning of family.

Because it incarnates the covenant. God wants us to have an earthly spirituality. These are carefully chosen words. Faith has to be fleshed out to be real. The Christian message is that God became a man. God didn’t become just another spirit. The Word became flesh and dwelt among us (John 1:14). Spirit became body. In marriage, too, spirit must become body. Love must become incarnate. If in the church there are Word and sacrament, in a marriage there needs to be words and touch. Our society secularizes sex. It treats it as pure body, pure flesh—nothing more. There are no sins and no sexual perversions. The converse, just as wrong although sometimes thought to be Christian, is the problem of hyperspirituality. These Christians talk about God but either live uneasily with the physical or live a double life. Flesh (in the sense of the physical) and spirit have never been reconciled. Sex is looked down upon, almost as a necessary evil. Karl Barth once said that “sex without marriage is demonic.” Now we must say that marriage without sex is demonic too. In contrast to the sacralizing and the secularizing of sex, the Bible sacramentalizes sex. It does this by putting it in its rightful place: in the covenant. That does not mean that single people cannot be whole without sexual intercourse. As Smedes puts it, “Although virgins do not experience the climax of sexual existence, they can experience personal wholeness by giving themselves to other persons without physical sex. Through a life of self-giving—which is the heart of sexual union—they become whole persons. They capture the essence without the usual form” (1976, p. 34).

Sex and Prayer

Sexual spirituality and spiritual sexuality appear to be oxymorons, but not to those who have been converted to a full biblical perspective on sexuality. There is a deep reason for this. The desire for sexual union and the desire for God are intimately related. God is a God of love. God dwells in the covenant community of Father, Son and Holy Spirit, interpenetrating, mutually indwelling, living for and in one another, finding life in self-giving to the other—all ways of describing what the Orthodox fathers of the church in the fifth century described as perichoresis: the intercommunion of the Godhead in a nonhierarchical community of loving, mutual abiding. Made in the image of God (Genesis 1:26), humankind was built male and female for communion, created to long for mutual abiding, destined to find fulfillment in self-giving. Commenting on how the sexual appetite is so closely related to worship and prayer, Alan Ecclestone notes:

The primitive impulse to deify sexual love was not wholly misguided; it has all the features of great mystical experience, abandon, ecstasy, polarity, dying, rebirth and perfect union. . . . It prompts between human beings those features characteristic of prayer; a noticing, a paying attention, a form of address, a yearning to communicate at ever deeper levels of being, an attempt to reach certain communion with the other. (Wild, p. 23)

But there is an important corrective in Scripture: our sexuality arises from our godlikeness; our godlikeness does not arise from our sexuality. So this profound clue to our true dignity as God-imaging creatures, a clue written into our genetic code, our psychological structure and our spiritual nature, is an invitation to seek and worship God in spirit (truly in Spirit) and truth (John 4:23).

So prayer and sexuality are intimately related for both men and women, though differently so. Not surprisingly, many people find themselves sexually aroused when they pray, whether or not they are in the presence of someone of the opposite sex.

Sex and Singleness

Three biblical goals for our personal sexuality are (1) sexual freedom, (2) sexual purity and (3) sexual contentment. Sexual freedom does not mean freedom from constraint but freedom to express our sexuality fully and exclusively within the marriage covenant. When one is not yet married, or is called to the single life (see Singleness), sexual freedom allows us to appreciate the other sex and to welcome our sexual appetites but to refrain from full physical expression outside of the marriage covenant. What is seldom noted about self-control is that it is a byproduct of a prayerful life, the result of walking in the Spirit, and not something gained by steeling one’s will or “trying.”

Sexual purity is certainly not dull (read the Song of Songs). To live freely and with sexual purity, we must reduce the amount of stimulation we allow ourselves to receive from magazines, movies, videos and mass media. Job could say that he had made a covenant with his eyes not to look at a woman lustfully (Job 31:1), not an easy thing to do in a sexually saturated culture. Positively, we must increase our attention to God. In a shocking exposé in Leadership magazine, a onetime spiritual director anonymously confided his battle with pornography and perverted sexual behavior. While he found that his attempts at trying to become pure through self-determination and passionate prayers of repentance failed, he was delivered at last by the simple recognition that his addiction to sex was shortchanging his intimacy with God. Love of God, that expulsive power of a new affection, purged lesser loves and even lust.

Sexual contentment, rather than sexual fulfillment, is a worthy Christian goal. The secret of contentment for Paul and ourselves is the practice of thanksgiving and continuing dependence on God (Phil. 4:6, 13). Thanksgiving is essential for single people who will be tempted to seek fulfillment mainly in themselves (see Masturbation) or in dating relationships that are impure. Single people will find their sexual repose by directing their love with all of its passion to the loving community of Father, Son and Holy Spirit, through which literally we experience God as our spouse (Isaiah 54:5).

In conclusion, sex is contemplative. This most down-to-earth daily stirring within us invites us heavenward. It does this by insisting through the very fibers of our being that we were built for love and built for the God who is love. It causes us daily to wonder at the mystery of complementarity, inviting us into a social experience in which there is more unity because of the diversity of male and female, just as God is more one because God is three. It demands of us more than raw, unaided human nature can deliver, a life of self-sacrifice and abiding contentment, qualities that can come only by practicing the presence of God. Finally, it invites us to live for God and his kingdom. As C. S. Lewis once said, if we find that nothing in this world and life fully satisfies us, it is a powerful indication that we were made for another life and another world. In some way beyond our imagination, human marriage will be transcended (Matthew 22:30) and fulfilled. Indeed, we will not give or receive in marriage because we will all be married in the completely humanized new heaven and new earth, where God’s people daily delight in being the bride of God (Rev. 19:7; Rev. 21:2).

» See also: Abuse

» See also: Body

» See also: Calling

» See also: Contraception

» See also: Family

» See also: Homosexuality

» See also: Love

» See also: Marriage

» See also: Masturbation

» See also: Singleness

References and Resources

D. Leckey, A Family Spirituality (New York: Crossroad, 1982); M. Mason, The Mystery of Marriage (Portland, Ore.: Multnomah, 1985); R. Rohr, “An Appetite for Wholeness,” Sojourners, November 1982, 30-32; L. Smedes, Mere Morality (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1983); L. Smedes, Sex for Christians (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1976); R. P. Stevens, Married for Good: The Lost Art of Remaining Happily Married (Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity Press, 1986, portions quoted with permission); H. Thielicke, “Mystery of Sexuality,” in Are You Nobody? (Richmond, Va.: John Knox, 1965); Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologia, trans. Fathers of the English Dominican Province, vol. 4 (New York: Benzigle Brothers, 1948); Vancouver Symphony Orchestra Programme Notes, March 13, 1983; E. Wheat, Intended for Pleasure (Old Tappan, N.J.: Fleming H. Revell, 1977); R. Wild, Frontiers of the Spirit: A Christian View of Spirituality (Toronto: Anglican Book Centre, 1981).

—R. Paul Stevens